Op het eerste gezicht is dit een heel curieuze voorstelling. Er gebeurt zoveel dat je bijna niet weet waar je moet kijken. Een man in luxe nachttenue snuffelt verlekkerd aan een bosje bloemen vanuit zijn hemelbed, terwijl een rijk uitgedoste figuur rechts van hem zich laaft aan rookpluimen. Een rondboog boven hem geeft een doorkijkje naar een meer verheven tafereel. Een geestelijke doet een brandoffer van een (ongedefinieerd) dier. Linksboven zwaait een man in pij een wierookvat richting een altaar.

Guillaume Collaert, naar Nicolaas van der Horst, ‘Allegorie van de reuk’, ca. 1610 (voor 1630).

We hebben hier te maken met een bijzondere uitvoering van een allegorie van de reuk door Guillaume Collaert naar Nicolaas van der Horst uit de vroege 17de eeuw. Waar vaak erotische, culinaire of andere banale aspecten van de reuk worden uitgelicht in voorstellingen van dit zintuig (zoals het verschonen van poepluiers), spelen in deze prent religieuze en medische functies van geur de hoofdrol.

Om dit te begrijpen heeft de lezer eerst achtergrondinformatie nodig over de dramatisch verschillende manier, waarop er over de reuk werd gedacht in de zeventiende eeuw.

Ten eerste was er – tot de ontdekking van Pasteur – geen kennis over ziektekiemen of over moleculen. Dat betekent dat de lucht werd voorgesteld als een zogenaamd ‘fluidum’. Stond die lucht te lang stil, dan bestond de kans dat deze verziekt raakte en kon gaan stinken. Stank werd niet alleen gezien als manifestatie van ‘inelastische lucht’ zoals Alain Corbin ons leert (1), maar ook als de oorzaak van ziekte en de verspreiding ervan. Dit geloof staat bekend als de ‘miasma-theorie’ en het werd alom geaccepteerd en gepraktiseerd door zowel de armste sloeber als de meest geleerde dokter. Om de lucht weer gezond te maken, volstonden sterk ruikende en zoete geuren, zoals kaneel, boomharsen en andere planten (zie ook mijn blog over de geurende medicijnen uit deze apothekerskast van het Rijksmuseum). Mensen van lagere komaf moesten het doen met de geur van geiten, azijn en rozemarijn.

De man in bed is waarschijnlijk een hooggeplaatste figuur die als remedie tegen een onbekende ziekte aan bloemen ruikt. Dat is plausibel omdat een van de afgebeelde bloemen heel duidelijk een ‘muurbloem’ betreft die speciaal in Europa werd geplant als ziektebestrijder.

Muurbloem. De vier bladeren die elkaar overlappen zijn duidelijk te herkennen in de prent.

Het inzetten van geuren als remedie was niet ongebruikelijk en kent een langere traditie. We zien bijvoorbeeld in de aantekeningen van de lijfarts van Willem van Oranje dat hij geregeld geurige medicamenten voorschreef. Toen de prins in 1574 leed aan ernstige buikloop (wat op zichzelf al de nodige geuren voor de geestesneus oproept die een allegorie waardig zijn), onderzocht Pieter van Foreestus eerst met al zijn zintuigen diens urine, alvorens mede te delen dat de prins het beste wijn met kaneel kon gaan drinken. Groene takken van loof in zijn kamer zouden de zieke lucht doen verfrissen (2). Na een paar dagen knapte de prins inderdaad op. Deze jongeman in zwart-wit ziet er blakend uit: hebben de geuren hun werk al gedaan?

Guillaume Collaert, uitsnede van ‘Allegorie van de reuk’ met bloemruikende man.

In ‘onze’ prent wordt de lucht daarnaast begeurd – en dus gezond gemaakt – door een ‘brûle-parfum’ of een parfumbrander. De opstijgende pluimen gaan een mooie beeldrijm aan met de veren in de hoed van de edele. Onderin werd de hittebron geplaatst met luchtgaten voor voldoende zuurstof. Typische geurstoffen om hiervoor te gebruiken waren houtsoorten zoals ceder, en harsen zoals labdanum (cisteroos), mirre en wierook. De openingen bovenin zorgden ervoor dat de geur zich kon verspreiden.

Guillaume Collaert, uitsnede van ‘Allegorie van de reuk’ met brûle-parfum en rechts een rijkelijk gedecoreerde parfumbrander van Desiderio da Firenze uit ca. 1540, beide uit de collectie van het Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Behalve in de medische zorg, werd geur ingezet in religieuze praktijken, zoals bij het ‘bewieroken’ van heilige plaatsen. Linksboven in de allegorische prent van Collaert zwaait een figuur met een wierookvat. Hierin bevindt zich smeulende hars, waarschijnlijk van wierook. Deze vaak in de Bijbel genoemde substantie bestond uit de hars van de – mogelijk uit Ethiopië afkomstige – olibanum; een zoetruikende stof met licht peperige en citrische noten van de Boswellia die nog steeds in de katholieke kerk wordt gebruikt. Zoetgeurende lucht werd kennelijk niet alleen als gezond ervaren, maar ook als manifestatie van het goddelijke. De methode van het branden van harsen om de goden te eren, werd door de Romeinen ‘per fumum’ genoemd, waaruit ons woord voor het meer banale ‘parfum’ is afgeleid.

Guillaume Collaert, uitsnede van ‘Allegorie van de reuk’ met reukoffer.

Ook een brandoffer was een manier om de neusgaten van God te bereiken. Direct na het bereiken van land, doet de oud-testamentische Noach bijvoorbeeld een offer van ‘rein vee’, hier verbeeld door Caspar Luyken. De rookpluimen vielen in goede aarde: “de geur van de offers behaagde de Heer”, staat vermeld in Genesis.

Cranach, ‘Offer van Noach na de zondvloed’, 1712.

Het offer op de prent van Collaert is dat van een dier dat zijn noodlot nederig lijkt te aanvaarden, terwijl een aantal honden (uiteraard ook verwijzingen naar de reuk) toekijken. Een biddende vrouw kijkt in hoopvolle verwachting toe. Mogelijk wordt gebeden voor het herstel van een zieke.

Guillaume Collaert, uitsnede van ‘Allegorie van de reuk’ met brandoffer.

Natuurlijk waren gezondheid en religie nog niet zo duidelijk van elkaar gescheiden zoals ze dat nu zijn. In deze prent zijn beide functies verweven. De glimlach van de bloemruikende man en de luxe kledij van de mannen onderin de prent, lijken ook een waarschuwing te zijn. Gebruiken zij de geuren misschien vooral voor aardse genoegens? De voorstelling mag dan een allegorie van de reuk zijn, maar bevat in feite ook een vanitas-boodschap: ‘memento mori’, of ‘denk eraan dat gij zult sterven’. Ruik dus niet in ijdelheid, want de beste geuren zijn aan God voorbehouden.

bij verwijzing naar dit blog graag mijn naam (Caro Verbeek) en de titel van dit artikel en mijn blog (Futuristscents) noemen.

Author sniffing Mendesian

By scent historian Caro Verbeek (caro@caroverbeek.nl)

Read the most accurate, detailed interview with Dora Goldsmith about the olfactory reconstruction of this enigmatic perfume so far.

Author sniffing Mendesian

By scent historian Caro Verbeek (caro@caroverbeek.nl)

Read the most accurate, detailed interview with Dora Goldsmith about the olfactory reconstruction of this enigmatic perfume so far.

Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra (with her tiny nose)

There is something enigmatic and immensely powerful about the sense of smell. It doesn’t just transport us to our personal past, like Marcel Proust demonstrated in his novel ‘In Search of Lost Time’. According to neuroscientist Richard Stevenson, no other sense is capable of yielding such a strong historical sensation, even if we have never smelled the scent in question before.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that when I – a scent historian – read about Dora Goldsmith’s and Dr. Sean Coughlin’s recreation of the famous Mendesian – a perfume allegedly used by Cleopatra herself – I was close to euphoric.

Recently I was lucky enough to smell it myself, after visiting Dora Goldsmith in Berlin, where she works on her PhD on ancient Egyptian smells at the Freie Universität. I must say the scent evoked very sensory and lively images of Cleopatra. It made her a living and breathing human being, instead of a distant legendary character numerous films and books are based on. To my nose the scent was incredibly voluminous, red-coloured, strong, warm, rich, sweet and slightly bitter. A perfume fit for an elegant gala.

Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra (with her tiny nose)

There is something enigmatic and immensely powerful about the sense of smell. It doesn’t just transport us to our personal past, like Marcel Proust demonstrated in his novel ‘In Search of Lost Time’. According to neuroscientist Richard Stevenson, no other sense is capable of yielding such a strong historical sensation, even if we have never smelled the scent in question before.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that when I – a scent historian – read about Dora Goldsmith’s and Dr. Sean Coughlin’s recreation of the famous Mendesian – a perfume allegedly used by Cleopatra herself – I was close to euphoric.

Recently I was lucky enough to smell it myself, after visiting Dora Goldsmith in Berlin, where she works on her PhD on ancient Egyptian smells at the Freie Universität. I must say the scent evoked very sensory and lively images of Cleopatra. It made her a living and breathing human being, instead of a distant legendary character numerous films and books are based on. To my nose the scent was incredibly voluminous, red-coloured, strong, warm, rich, sweet and slightly bitter. A perfume fit for an elegant gala.

Dora Goldsmith putting Mendesian on her skin during an interview with the BBC

Goldsmith was willing to answer some questions about the reconstruction to shed some light on this mysterious matter from her professional practice as an Egyptologist:

Dora Goldsmith putting Mendesian on her skin during an interview with the BBC

Goldsmith was willing to answer some questions about the reconstruction to shed some light on this mysterious matter from her professional practice as an Egyptologist:

Installation of the ingredients of the Mendesian. Among the main ingredients are myrrh, cinnamon, and cinnamon cassia. Copyright Dora Goldsmith.

Installation of the ingredients of the Mendesian. Among the main ingredients are myrrh, cinnamon, and cinnamon cassia. Copyright Dora Goldsmith.

Installation of the ingredients of the Metopian, which was based on Mendesian. Copyright Dora Goldsmith.

Installation of the ingredients of the Metopian, which was based on Mendesian. Copyright Dora Goldsmith.

Montessori stated that without training the senses the world would be unknowable to mankind. Even moral judgment would be impossible. Without sensory perception, it is after all impossible to understand the relationship between words and objects, between our inner and external existence. She made her young students touch, smell and taste and even weigh objects and relate their findings to vocabulary and to emotions.

These two iconic figures – Nietzsche and Montessori – weren’t even the firsts – to support the thought that sensing, and smelling in particular could lead to profound knowledge.

And one of them comes from an entirely different unexpected field. Namely from religion.

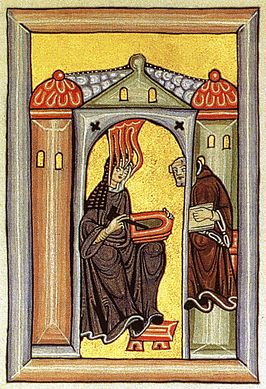

Hildegard von Bingen was a 12th century, highly respected and well-known mystic, even though she was a woman. She was able to read and write and considered an intellectual. In fact, besides being a mystic this German Benedictine Abbess was a writer, composer, philosopher and visionary. Although retrospectively one might rather say ‘olfactionary’.

One of her most striking thoughts was, and I quote:

Montessori stated that without training the senses the world would be unknowable to mankind. Even moral judgment would be impossible. Without sensory perception, it is after all impossible to understand the relationship between words and objects, between our inner and external existence. She made her young students touch, smell and taste and even weigh objects and relate their findings to vocabulary and to emotions.

These two iconic figures – Nietzsche and Montessori – weren’t even the firsts – to support the thought that sensing, and smelling in particular could lead to profound knowledge.

And one of them comes from an entirely different unexpected field. Namely from religion.

Hildegard von Bingen was a 12th century, highly respected and well-known mystic, even though she was a woman. She was able to read and write and considered an intellectual. In fact, besides being a mystic this German Benedictine Abbess was a writer, composer, philosopher and visionary. Although retrospectively one might rather say ‘olfactionary’.

One of her most striking thoughts was, and I quote:

The most famous saint who died in an odour of sanctity was Teresa d’ Avila, best known for the sculpture Bernini created hundreds of years later, capturing one of her visions in stone, with an eternal orgasmic expression on her face.

“The moment she died her bedside attendants said the room filled with the scent of roses that grew to saturate the building. The convent smelt like it had erupted into bloom and cascades of invisible blossoms poured from the windows”, activist and scent expert Nuri McBride wrote so eloquently.

And everyone knew and felt, just by inhaling, that Teresa was a Saint of the highest order.

The most famous saint who died in an odour of sanctity was Teresa d’ Avila, best known for the sculpture Bernini created hundreds of years later, capturing one of her visions in stone, with an eternal orgasmic expression on her face.

“The moment she died her bedside attendants said the room filled with the scent of roses that grew to saturate the building. The convent smelt like it had erupted into bloom and cascades of invisible blossoms poured from the windows”, activist and scent expert Nuri McBride wrote so eloquently.

And everyone knew and felt, just by inhaling, that Teresa was a Saint of the highest order.

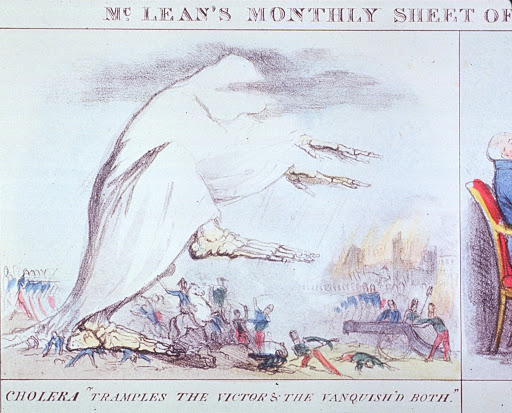

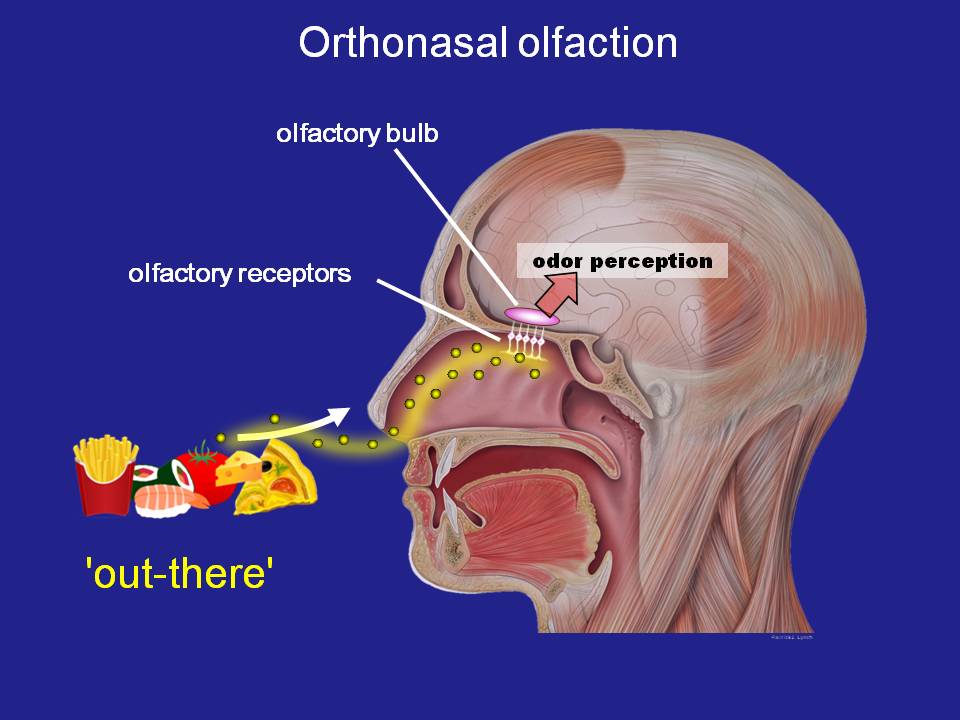

Some 600 years after Hildegard von Bingen’s era, scents weren’t only considered the highest manifestations of divine presence, learning from smells could even save lives here on earth.

Alain Corbin reconstructed the social history of 18th century France through the perspective of the nose, or with an olfactory gaze. Physicians and medics and other professionals at the time were employed by the city to detect, describe and eliminate the foul and dangerous smells of the French capital to safeguard public health. This means that these professionals entertained a vast and more or less objective olfactory vocabulary.

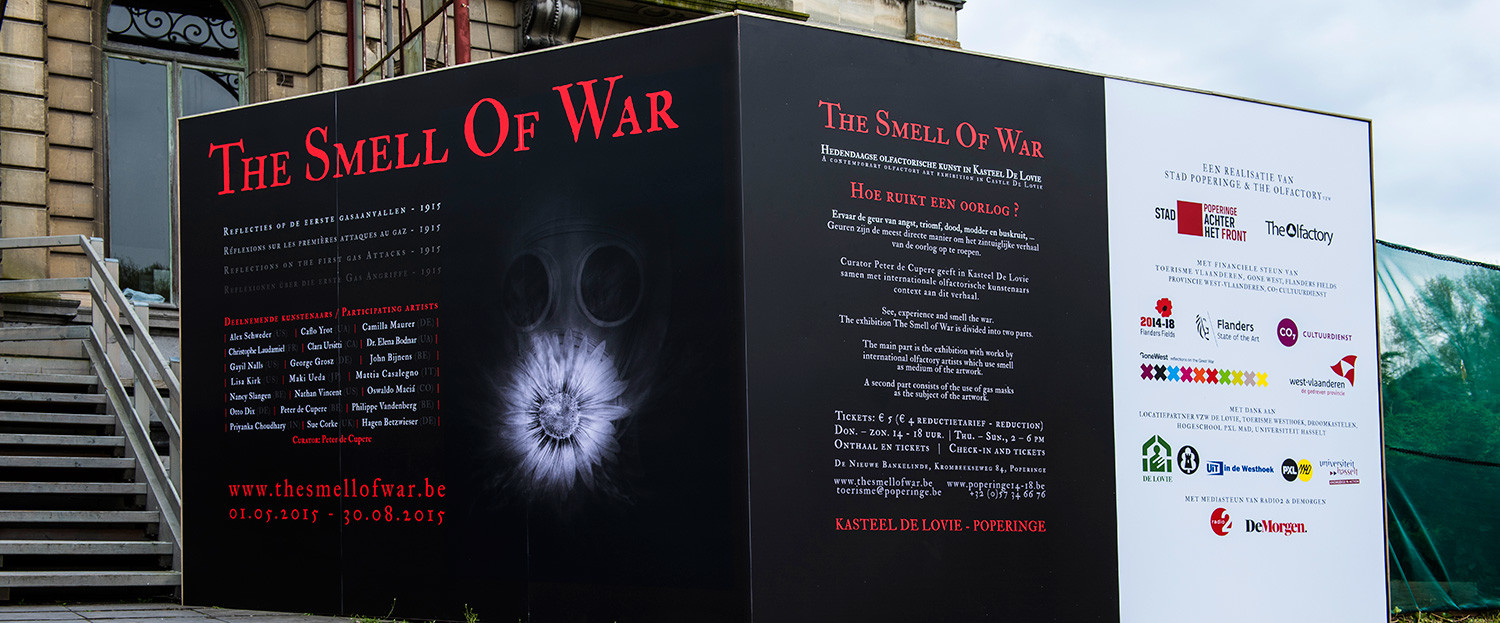

Finally I would like to mention the realm of ‘visual art’. Unlike classic art history books (usually) convey, the sense of smell played a role in symbolism, futurism, dadaism, surrealism, arte povera and so on. Within futurism olfaction was even embedded in the political and societal theories and art practices of this first true avant-garde movement. In line with their avant-garde approach – yet to my surprise – the first artist within this movement to not just write about the sense of smell, but to actually address it, was…… a woman!

As early as 1912 the French affiliated artist Valentine de Saint-Point performed exotic dances accompanied by wafts of scented smoke, in order to create a synaesthetic and multi-sensory Total Work of Art. It would take almost 20 years until Marinetti – the leader of the futurist movement – made use of perfume in one of his theatrical pieces.

Some 600 years after Hildegard von Bingen’s era, scents weren’t only considered the highest manifestations of divine presence, learning from smells could even save lives here on earth.

Alain Corbin reconstructed the social history of 18th century France through the perspective of the nose, or with an olfactory gaze. Physicians and medics and other professionals at the time were employed by the city to detect, describe and eliminate the foul and dangerous smells of the French capital to safeguard public health. This means that these professionals entertained a vast and more or less objective olfactory vocabulary.

Finally I would like to mention the realm of ‘visual art’. Unlike classic art history books (usually) convey, the sense of smell played a role in symbolism, futurism, dadaism, surrealism, arte povera and so on. Within futurism olfaction was even embedded in the political and societal theories and art practices of this first true avant-garde movement. In line with their avant-garde approach – yet to my surprise – the first artist within this movement to not just write about the sense of smell, but to actually address it, was…… a woman!

As early as 1912 the French affiliated artist Valentine de Saint-Point performed exotic dances accompanied by wafts of scented smoke, in order to create a synaesthetic and multi-sensory Total Work of Art. It would take almost 20 years until Marinetti – the leader of the futurist movement – made use of perfume in one of his theatrical pieces.

The reason I mention all these historical examples is because:

The reason I mention all these historical examples is because:

‘Blikopeners’ (eye openers) distributing art historical smells during ‘Stedelijk Statements: Caro Verbeek – The Museum of Smells’, copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

By Caro Verbeek (caro@caroverbeek.nl)

For the fifth edition of

‘Blikopeners’ (eye openers) distributing art historical smells during ‘Stedelijk Statements: Caro Verbeek – The Museum of Smells’, copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

By Caro Verbeek (caro@caroverbeek.nl)

For the fifth edition of  Aromajockey Scentman performing, following the scent-scripts provided by the lecturers, copyright Stedelijk Museum, photo Ernst van Deursen

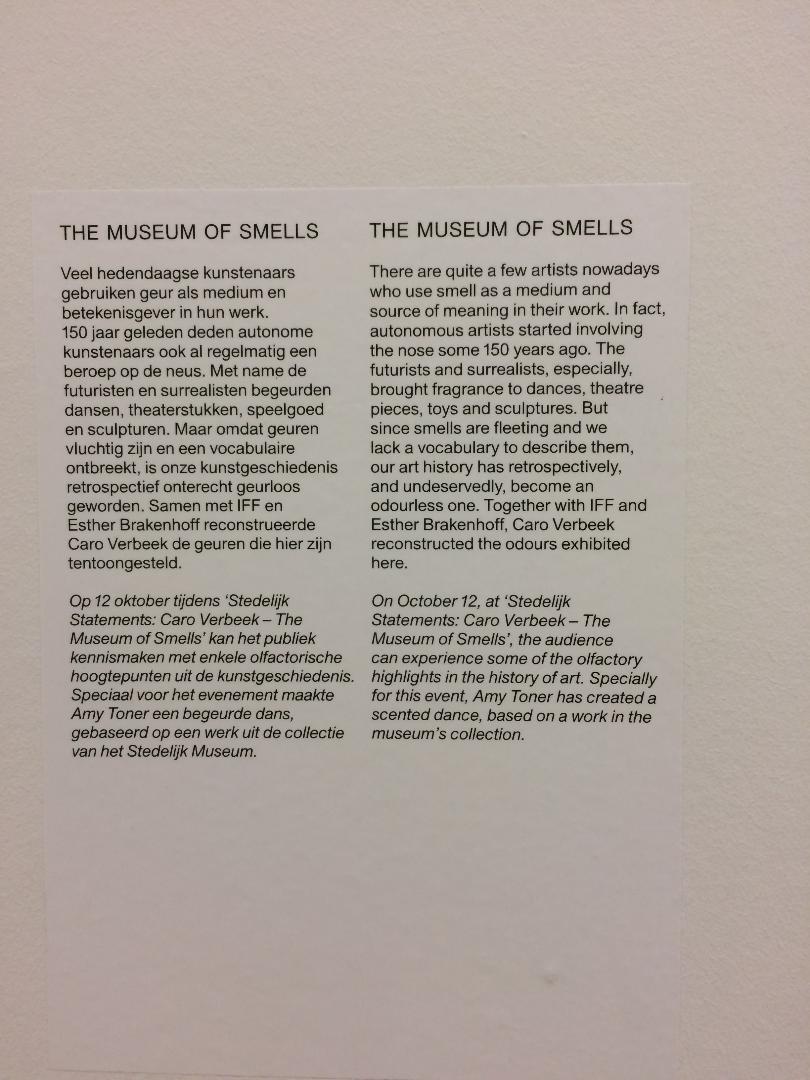

During the event there was a lecture by renowned olfactory artist Peter De Cupere, by literature scholar Piet Devos, and a performance by the artist-choreographer Amy Toner, performed by dancer Maroula Iliopoulou and scented live by aromajockey Scentman. During the intermission, visitors had the opportunity to smell different moments in art history. The goal was to explore the possibilities and challenges of presenting, critiquing, preserving and reconstructing historical and contemporary olfactory art in the museum.

Here are some pictures of the evening and exhibited smells (I wish I could digitally convey them to you all….) along with the texts that were presented in the galeries of the museum.

Aromajockey Scentman performing, following the scent-scripts provided by the lecturers, copyright Stedelijk Museum, photo Ernst van Deursen

During the event there was a lecture by renowned olfactory artist Peter De Cupere, by literature scholar Piet Devos, and a performance by the artist-choreographer Amy Toner, performed by dancer Maroula Iliopoulou and scented live by aromajockey Scentman. During the intermission, visitors had the opportunity to smell different moments in art history. The goal was to explore the possibilities and challenges of presenting, critiquing, preserving and reconstructing historical and contemporary olfactory art in the museum.

Here are some pictures of the evening and exhibited smells (I wish I could digitally convey them to you all….) along with the texts that were presented in the galeries of the museum.

The introductory text for the one day exhibition ‘The Museum of Smells’, copyright author, text and photo by author.

The introductory text for the one day exhibition ‘The Museum of Smells’, copyright author, text and photo by author.

Installing the art historical olfactory reconstructions at the Stedelijk Museum. Images on the pedestals were placed as visual documentation to accompany the scents on top. Photo by author

Installing the art historical olfactory reconstructions at the Stedelijk Museum. Images on the pedestals were placed as visual documentation to accompany the scents on top. Photo by author

Installation view of the exhibition where 5 scents were placed chronologically (1912 – 2015), ranging from Futurism to installation art.

I

Installation view of the exhibition where 5 scents were placed chronologically (1912 – 2015), ranging from Futurism to installation art.

I Scent no 1. Valentine de Saint Point dancing her choreography ‘Metachorie’, in Paris, 1912

Scent no 1. Valentine de Saint Point dancing her choreography ‘Metachorie’, in Paris, 1912

Scent no 1 on sniff:

Valentine de Saint Point, Métachorie (1913)

olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

Métachorie was the first futurist performance that involved fragrances. In combination with the music and decor, they formed a synthesis with the movements by dancer and choreographer De Saint Point. A critic who attended the performance described the fragrant smoke curtains as exotic, which around the fin-de-siècle implies the then-recently Westernized colonial fragrances of – among others – patchouli and sandalwood (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

photo by author

Scent no 1 on sniff:

Valentine de Saint Point, Métachorie (1913)

olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

Métachorie was the first futurist performance that involved fragrances. In combination with the music and decor, they formed a synthesis with the movements by dancer and choreographer De Saint Point. A critic who attended the performance described the fragrant smoke curtains as exotic, which around the fin-de-siècle implies the then-recently Westernized colonial fragrances of – among others – patchouli and sandalwood (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

photo by author

Scholar and expert of sensory literature Piet Devos sniffing ‘Metachorie’

Photo by Justus Tomlow

Scholar and expert of sensory literature Piet Devos sniffing ‘Metachorie’

Photo by Justus Tomlow

Scent no 2 on sniff:

Eau de Cologne

From La Cucina Futurista/ the Futurist Cookbook (1932)

Olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

In the thirties, the futurists organized politically tinted artistic banquets, where no sense was left unaddressed. For example, they spread the fragrances of ozone (as a reference to electricity) and Eau de Cologne, which is originally an Italian toilet water. The latter had connotations of war, as it was used to treat wounds at the front. Furthermore, ‘Aqua di Colonia’ literally means ‘colonial water’ in Italian (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Scent no 2 on sniff:

Eau de Cologne

From La Cucina Futurista/ the Futurist Cookbook (1932)

Olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

In the thirties, the futurists organized politically tinted artistic banquets, where no sense was left unaddressed. For example, they spread the fragrances of ozone (as a reference to electricity) and Eau de Cologne, which is originally an Italian toilet water. The latter had connotations of war, as it was used to treat wounds at the front. Furthermore, ‘Aqua di Colonia’ literally means ‘colonial water’ in Italian (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Scent no 3 on sniff:

Benjamin Peret, Odeurs du Brésil at the International Surrealist Exhibition, Galérie des Beaux Arts, Paris (1938)

olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

According to nose-witnesses Man Ray and Simone de Beauvoir, the 1938 surrealist exhibition strongly smelled of Brazilian coffee. During the opening, Benjamin Pérèt roasted coffee beans on an electric stove. Looking back, Marcel Duchamp described the aroma as an independent surrealist artwork. The fragrance may have been a reference to Brazil’s joining of the surrealist movement that year, or to the place where the surrealists were most commonly found: the café (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Scent no 3 on sniff:

Benjamin Peret, Odeurs du Brésil at the International Surrealist Exhibition, Galérie des Beaux Arts, Paris (1938)

olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

According to nose-witnesses Man Ray and Simone de Beauvoir, the 1938 surrealist exhibition strongly smelled of Brazilian coffee. During the opening, Benjamin Pérèt roasted coffee beans on an electric stove. Looking back, Marcel Duchamp described the aroma as an independent surrealist artwork. The fragrance may have been a reference to Brazil’s joining of the surrealist movement that year, or to the place where the surrealists were most commonly found: the café (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Scent no 4 on sniff:

Marcel Duchamp, First Papers of Surrealism, Reid Mansion, New York (1942)

olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

‘Vernissage consacré aux enfants jouant, à l’odeur du cèdre’ (Opening dedicated to children at play and the smell of cedar), said the invitation to the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism. The fragrance of cedar wood may have been a reference to the cigar boxes in which the artist – an avid smoker – kept his papers, and which he regularly used to create artist’s books and artworks. Even though one of the last nose witnesses was interviewed, he didn’t recollect a scent (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Scent no 4 on sniff:

Marcel Duchamp, First Papers of Surrealism, Reid Mansion, New York (1942)

olfactory reconstruction by IFF perfumer (2018)

‘Vernissage consacré aux enfants jouant, à l’odeur du cèdre’ (Opening dedicated to children at play and the smell of cedar), said the invitation to the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism. The fragrance of cedar wood may have been a reference to the cigar boxes in which the artist – an avid smoker – kept his papers, and which he regularly used to create artist’s books and artworks. Even though one of the last nose witnesses was interviewed, he didn’t recollect a scent (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Scent no 5 on sniff:

Esther Brakenhoff, Geurcapsule / Fragrance Capsule: Edward Kienholz, Beanery (1965), 2015

plastic and aromatic substances

This fragrance capsule is a visual and olfactory homage to Edward Kienholz’ art piece The Beanery, a replica of a bar in Los Angeles. Kienholz added smells to enhance the work’s realism. Brakenhoff’s clock-shaped capsule – a reference to the shape of the customers’ heads – contains a reconstruction of the smell Kienholz had in mind: ashes, stale beer, mothballs, rancid grease and urine.

Photo by author

Scent no 5 on sniff:

Esther Brakenhoff, Geurcapsule / Fragrance Capsule: Edward Kienholz, Beanery (1965), 2015

plastic and aromatic substances

This fragrance capsule is a visual and olfactory homage to Edward Kienholz’ art piece The Beanery, a replica of a bar in Los Angeles. Kienholz added smells to enhance the work’s realism. Brakenhoff’s clock-shaped capsule – a reference to the shape of the customers’ heads – contains a reconstruction of the smell Kienholz had in mind: ashes, stale beer, mothballs, rancid grease and urine.

Photo by author

View of the interior of ‘The Beanery’ (1965), by Edward Kienholz, collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

photo Wikimedia Commons

View of the interior of ‘The Beanery’ (1965), by Edward Kienholz, collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

photo Wikimedia Commons

A very precious and rare object on display:

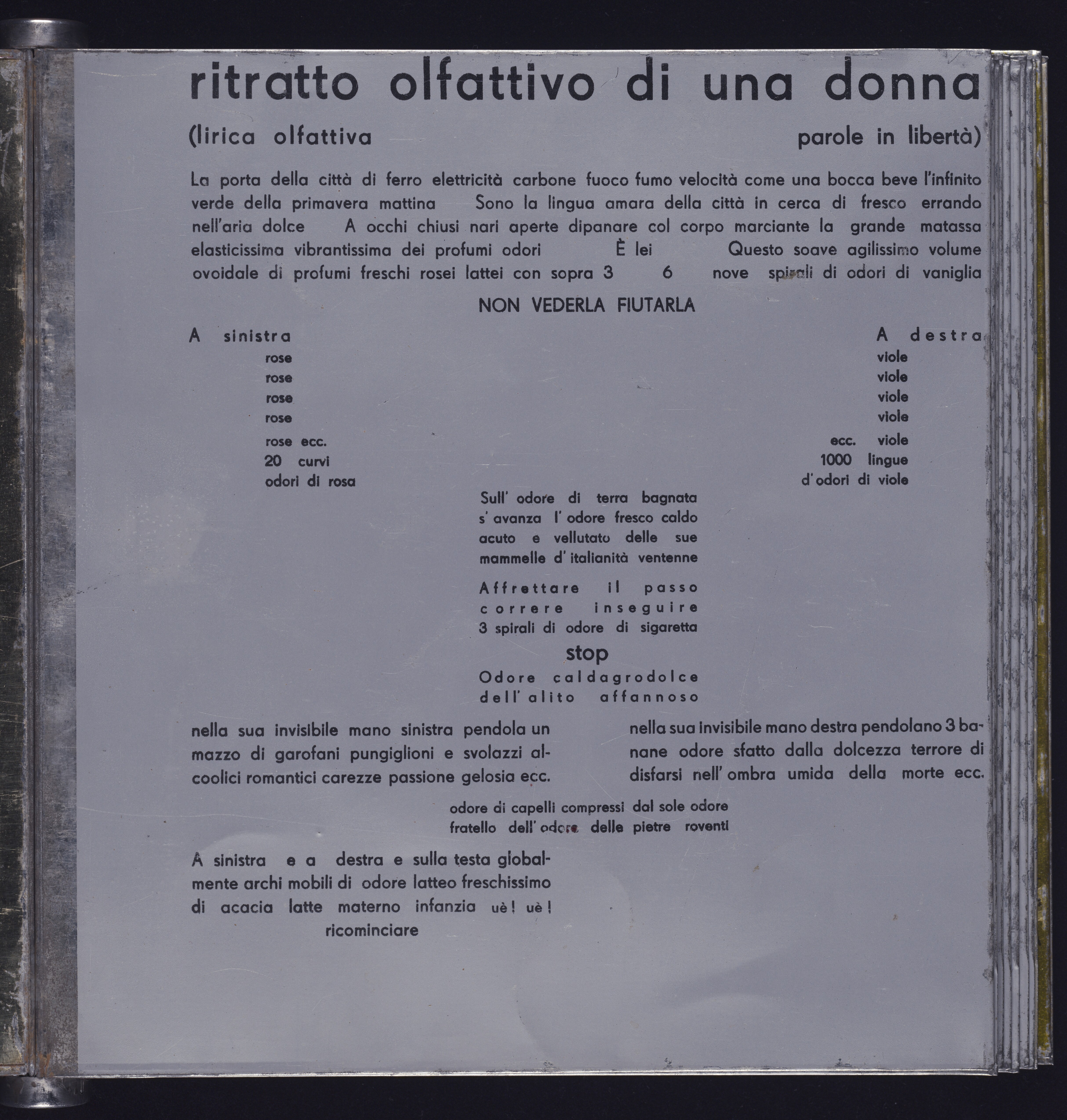

F.T. Marinetti and Tullio d’Albissola, Ritratto olfattivo di una donna/ Olfactory Portrait of a Woman

from: Parole in libertà futuriste olfattive tattili termiche/ Futurist Olfactory Tactile Thermal Words in Freedom, 1932

lithography on tin

This artist’s book, based on the idiom of the machine, is exceptionally sensorial. It feels cool, smooth and hard to the touch, with a metallic smell. Its contents also address the olfactory experience; in the exhibited poem, a man tracks the scents of the object of his lust. The smell of moist earth and milk suggest the conclusion: the birth of a child after a bout of love-making on the ground (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Photo by author

A very precious and rare object on display:

F.T. Marinetti and Tullio d’Albissola, Ritratto olfattivo di una donna/ Olfactory Portrait of a Woman

from: Parole in libertà futuriste olfattive tattili termiche/ Futurist Olfactory Tactile Thermal Words in Freedom, 1932

lithography on tin

This artist’s book, based on the idiom of the machine, is exceptionally sensorial. It feels cool, smooth and hard to the touch, with a metallic smell. Its contents also address the olfactory experience; in the exhibited poem, a man tracks the scents of the object of his lust. The smell of moist earth and milk suggest the conclusion: the birth of a child after a bout of love-making on the ground (source: C. Verbeek, In Search of Lost Scents, PhD, expected in 2019).

Photo by author

Installation view of the poem ‘Ritratto olfattivo di una donna’, 1932

photo by author

Installation view of the poem ‘Ritratto olfattivo di una donna’, 1932

photo by author

‘Ritratto olfattivo di una donna’, a poem on metal, the words positioned in the shape of a female body.

This poem is one of the very few avant-garde texts on scent expressed through movement as it speaks of mobile arches, moving volumes and spirals of scent (see a previous blog about that

‘Ritratto olfattivo di una donna’, a poem on metal, the words positioned in the shape of a female body.

This poem is one of the very few avant-garde texts on scent expressed through movement as it speaks of mobile arches, moving volumes and spirals of scent (see a previous blog about that  Photo by Camilla Greenwell

Photo by Camilla Greenwell Copyright Mediamatic

Copyright Mediamatic

Copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

Copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

Copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

Amy Toner’s contemporary choreography ‘Beneath Her Eyes’ (2018), performed by Maroula Iliopoulou. The performance was first staged at Mediamatic’s

Copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

Amy Toner’s contemporary choreography ‘Beneath Her Eyes’ (2018), performed by Maroula Iliopoulou. The performance was first staged at Mediamatic’s  At the beginning of the evening, a very pregnant and odour-sensitive researcher (…) talked about the role of smell in Futurism and Surrealism. ‘The scent, the scent alone is enough for us beasts’, Marinetti stated in 1909 in the founding manifesto of Futurism. The leader of the Futurists drew the attention to this lower sense which he would address much more often during his career. To him and his fellow artists the sense of smell represented a different kind of knowledge, namely intuition; a notion taken from Nietzsche. ‘Fiuto’ means both ‘acute sense of smell’ and ‘intuition’, so the English translation doesn’t really suffice. Paying attention to the sense of smell as an artistic medium defied the ocularcentric perspective of the bourgeoisie, which the Futurists despised, making their olfactory practices a political act in themselves.

In the next presentation, Peter de Cupere drew on his own experiences to explain the added value of working with scent, highlighting the challenges and limitations encountered in working with scent in a museum setting.

At the beginning of the evening, a very pregnant and odour-sensitive researcher (…) talked about the role of smell in Futurism and Surrealism. ‘The scent, the scent alone is enough for us beasts’, Marinetti stated in 1909 in the founding manifesto of Futurism. The leader of the Futurists drew the attention to this lower sense which he would address much more often during his career. To him and his fellow artists the sense of smell represented a different kind of knowledge, namely intuition; a notion taken from Nietzsche. ‘Fiuto’ means both ‘acute sense of smell’ and ‘intuition’, so the English translation doesn’t really suffice. Paying attention to the sense of smell as an artistic medium defied the ocularcentric perspective of the bourgeoisie, which the Futurists despised, making their olfactory practices a political act in themselves.

In the next presentation, Peter de Cupere drew on his own experiences to explain the added value of working with scent, highlighting the challenges and limitations encountered in working with scent in a museum setting.

All participants: Caro Verbeek, Piet Devos, Amy Toner, Maroula Iliopoulou, Peter de Cupere, Jorg Hempenius (Aromajockey Scentman), copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

(more information about these lectures on olfactory and ephemeral heritage will follow in another blog in which I interview Peter de Cupere, Piet Devos and Amy Toner)

by Caro Verbeek, scent and art historian

for more information on smell in museums, scent reconstructions or olfactory history send a message to caro@caroverbeek.nl

All participants: Caro Verbeek, Piet Devos, Amy Toner, Maroula Iliopoulou, Peter de Cupere, Jorg Hempenius (Aromajockey Scentman), copyright Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, photo Ernst van Deursen

(more information about these lectures on olfactory and ephemeral heritage will follow in another blog in which I interview Peter de Cupere, Piet Devos and Amy Toner)

by Caro Verbeek, scent and art historian

for more information on smell in museums, scent reconstructions or olfactory history send a message to caro@caroverbeek.nl

By art and scent historian Caro Verbeek

In 1481/1482 renaissance artist Botticelli finished the immense painting ‘La Primavera’, which he created for the occasion of the marriage of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici. It is one of the most famous paintings in the world and can be admired in its place of ‘birth’ Florence.

The flowers and plants in Primavera (spring) are an important and very striking part of this work of art. The antique gods Mercury (to the left) and Venus (in the center) are surrounded by colourful fruit trees with juicy oranges that arise from a fresh green meadow, and flowers in bloom are scattered all over the place. Botticelli portrayed these flowers with such great care and detail that they are actually recognizable as real specimens. Guido Moggi – former director of the Botanical Garden in Florence –and Mirella Levi d’Ancona identified almost 200 of them in 1984.

Aromatic symbols

These (and most other) scholars merely discuss the visual beauty of the botanical specimens and the myths they were mentioned in as an explanation for Botticelli’s choice of the depicted flora. But what about their aromatic dimension? This painting is one big open window exuding the most wonderful and characteristic scents of Tuscany in spring. Is there an olfactory iconography to this work of art? It can be argued Botticelli has intentionally added olfactory – yet visually represented – symbols.

Botticelli most probably took several renaissance texts as a starting point. In ‘De Rerum natura’ by Lucretius, there is a very clear reference to both the visual and olfactory appeal of spring, which is represented by the goddess Venus. I found the following English translation:

By art and scent historian Caro Verbeek

In 1481/1482 renaissance artist Botticelli finished the immense painting ‘La Primavera’, which he created for the occasion of the marriage of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici. It is one of the most famous paintings in the world and can be admired in its place of ‘birth’ Florence.

The flowers and plants in Primavera (spring) are an important and very striking part of this work of art. The antique gods Mercury (to the left) and Venus (in the center) are surrounded by colourful fruit trees with juicy oranges that arise from a fresh green meadow, and flowers in bloom are scattered all over the place. Botticelli portrayed these flowers with such great care and detail that they are actually recognizable as real specimens. Guido Moggi – former director of the Botanical Garden in Florence –and Mirella Levi d’Ancona identified almost 200 of them in 1984.

Aromatic symbols

These (and most other) scholars merely discuss the visual beauty of the botanical specimens and the myths they were mentioned in as an explanation for Botticelli’s choice of the depicted flora. But what about their aromatic dimension? This painting is one big open window exuding the most wonderful and characteristic scents of Tuscany in spring. Is there an olfactory iconography to this work of art? It can be argued Botticelli has intentionally added olfactory – yet visually represented – symbols.

Botticelli most probably took several renaissance texts as a starting point. In ‘De Rerum natura’ by Lucretius, there is a very clear reference to both the visual and olfactory appeal of spring, which is represented by the goddess Venus. I found the following English translation:

Venus – in the centre of the painting – is surrounded by myrtle, beautifully defined against a pale blue sky. It is highly likely this choice was informed by olfaction. Myrtle – with its very strong scent – was well known in ancient Greece and Rome for its healing properties and associated to the island of Cyprus, the birth place of Venus. It was used as a fragrant offering to statues representing the goddess of Love, known in Greece as Aphrodite. Its perfume is both fresh and warm, sweet yet savoury, and smells slightly medicinal or anti-septic (which it actually is).

In 2006 archeologist Maria Rosario Belgiorno excavated an

Venus – in the centre of the painting – is surrounded by myrtle, beautifully defined against a pale blue sky. It is highly likely this choice was informed by olfaction. Myrtle – with its very strong scent – was well known in ancient Greece and Rome for its healing properties and associated to the island of Cyprus, the birth place of Venus. It was used as a fragrant offering to statues representing the goddess of Love, known in Greece as Aphrodite. Its perfume is both fresh and warm, sweet yet savoury, and smells slightly medicinal or anti-septic (which it actually is).

In 2006 archeologist Maria Rosario Belgiorno excavated an