Bernardo Fleming from IFF examines the scent of Mondrian’s New York studio.

Technically, scents consist of a collection of molecules that penetrate our nostrils. Scents, elusive as they may seem, are a tangible reflection of materials, activities, events, and thus of eras and places. Yet, a scent is more than just its physical components; once odor molecules reach our noses, they unlock an immense, previously hidden mental space within us, composed of memories and emotions. A single scent can convey more than a thousand images, and a single whiff can transport us back to a distant past. Mondrian himself was sensitive to such stimuli, possibly due to his grandfather’s profession as a perfumer (and wigmaker). For example, in 1910, he wrote to his close friend Aletta de Iong:

I think flowers are such an extraordinarily wonderful thing. There were such masses on that square behind Boymans this week! The smell of it also makes me feel very strange.

The photographer Hannes Wallrafen (who turned blind later in life) smells the scent of Mondrian’s Paris studio.

In Mondrian’s 150th birth anniversary year (2022), curator Caro Verbeek of the Kunstmuseum Den Haag wondered if it would be possible to reconstruct the scent of Mondrian’s living environments. This question led to even more intriguing inquiries: what might the bygone scents of Mondrian’s studios in Amsterdam, Paris, and New York reveal to us? How do they relate to the changing world in which the artist lived and created? Could we even, perhaps, smell his journey toward abstraction?

Thanks to a collaboration with IFF perfumers, visitors have been able to experience these scents themselves for several years through a permanent olfactory exhibit in the “Mondrian & De Stijl” section of the museum. Based on research by curator Verbeek, IFF perfumers Anh Ngo and Birgit Sijbrands, under the guidance of Bernardo Fleming, created a scentscape of three distinct fragrances. Visitors frequently report that the compositions make them feel as though they are standing alongside Mondrian in his studio, rather than merely observing his work. This has fostered a deeper empathy for him as a flesh-and-blood individual.

Colonial Aromas of Amsterdam

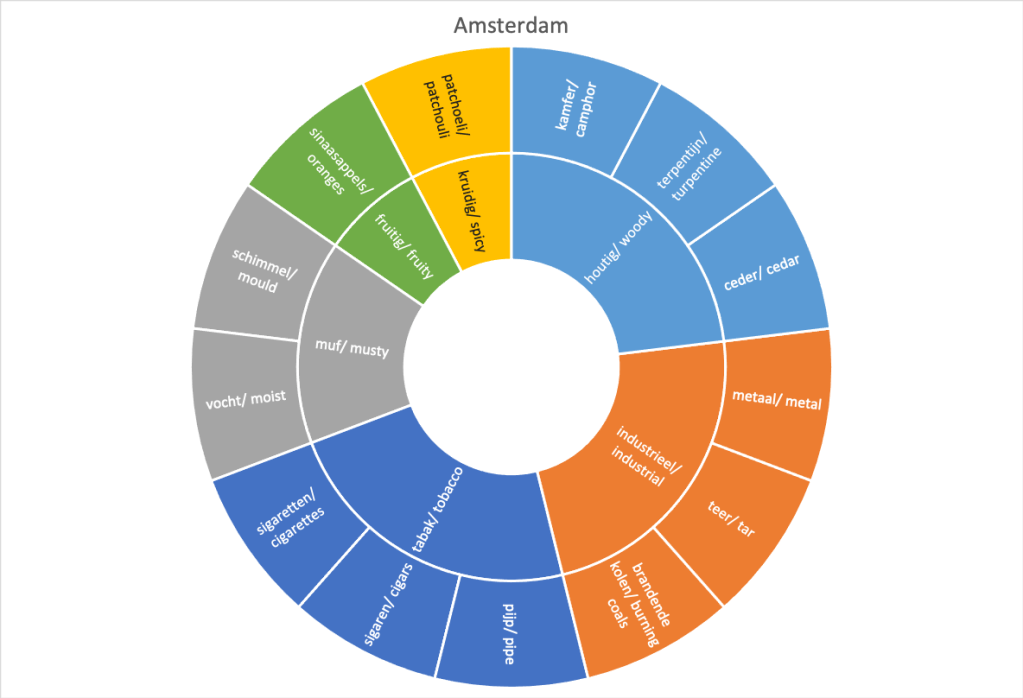

Scent wheel of Mondrian’s studio in Amsterdam, ca. 1909, copyright Caro Verbeek.

At the beginning of his artistic career, Mondrian lived in Amsterdam, where he studied at the Rijksacademie. At this time, he worked in a traditional naturalistic style based on external observation—what he saw around him. He painted still lifes, landscapes, and windmills, often in the dark tones favored by the Hague School. His studio at Sarphatipark was typical of other artists’ spaces of the time, featuring heavy wooden furniture, a coal stove, and a variety of collected objects, such as brassware, masks, vases, Japanese prints, cashmere shawls and Persian carpets.

These cashmere shawls – of which he owned several – likely emitted the strong scent of patchouli—a plant with an insect-repellent fragrance. Meanwhile, his textiles likely carried a refreshing camphor aroma, another scent used to protect fabrics. Such aromas were highly exotic to Western noses at the time, having become collectively available to the Dutch through colonialism and globalization.

Patchouli, WikiMedia Commons.

Activities in the studio also left their mark on its scent. Mondrian and visiting artists smoked tobacco, including cigars, pipes, and cigarettes. The invigorating, sharp scent of turpentine—an essential material for painters—likely dominated the air. A faint, damp mustiness, characteristic of Amsterdam houses with their canals and lack of cavity walls, would have formed the base note of the space’s aroma.

Of course, the studio didn’t smell the same every day. Mondrian’s activities created olfactory rhythms, such as when he painted a wall black in 1909. He wrote to Aletta de Iong:

Since I blackened a wall of the studio with coal tar, it smells so much of tar that you might get a headache if I just leave. I thought the air would go away sooner. So should we postpone until next week?

Mondrian would encounter these and other scents again in Paris, alongside entirely new ones.

The Industrial Atmosphere of Paris

Scent wheel of Mondrian’s studio in Paris, ca. 1919, copyright Caro Verbeek.

In Paris, where Mondrian lived from 1912 to 1938 (with a break during World War I), his work began to take on the style for which he is now famous. Visual reality became less important as abstraction entered his art. His studio on Rue du Départ grew increasingly minimalist and orderly, reflecting his belief that rhythm and movement were closer to life than its visual representation, which he called “costume.” The studio held only essential items: lamps, furniture, painting tools, and a few ashtrays.

However, the industrial aromas of burning coal, heated metal, smoke, and steam from the nearby Gare Montparnasse likely intruded upon this pristine space. Mondrian had to cover his paintings when opening the windows to prevent a black film from forming on them. Visitors, though, did not seem to notice these industrial smells but instead remarked on the unpleasant odors in the staircase. The smell of tarred rope used as a banister was overwhelmed by the stench from a shared washbasin on the second floor. Michel Seuphor, Mondrian’s friend and art critic, remembered this odor vividly sixty years later:

The courtyard, where the entrance to Mondrian's studio was located, was very miserable. It smelled a bit in the stairwell […].

Painter Wim Schuhmacher also commented on the overwhelming smell:

On the second floor there was a sink for the entire floor and the sink was extremely dirty. Then you would have smelled all that stench and urine and then you came to Piet.

The transition from this foul-smelling space to Mondrian’s open, light-filled studio must have been a literal and figurative breath of fresh air. In winter, the studio smelled of burning coal—if one could afford it—and the city’s outdoor scents filtered in, as Mondrian described in 1920 in his ‘Groote Boulevards’ (Grand Boulevards):

The boulevard is more thought-concentrated. I see the colors and shapes. I hear the sounds. I feel the spring warmth, I smell the spring air, the gasoline, the perfumes, I taste the coffee.

Gare Montparnasse near Mondrian’s studio at the Rue du Départ, WikiMedia Commons.

A Hint of Freedom in New York

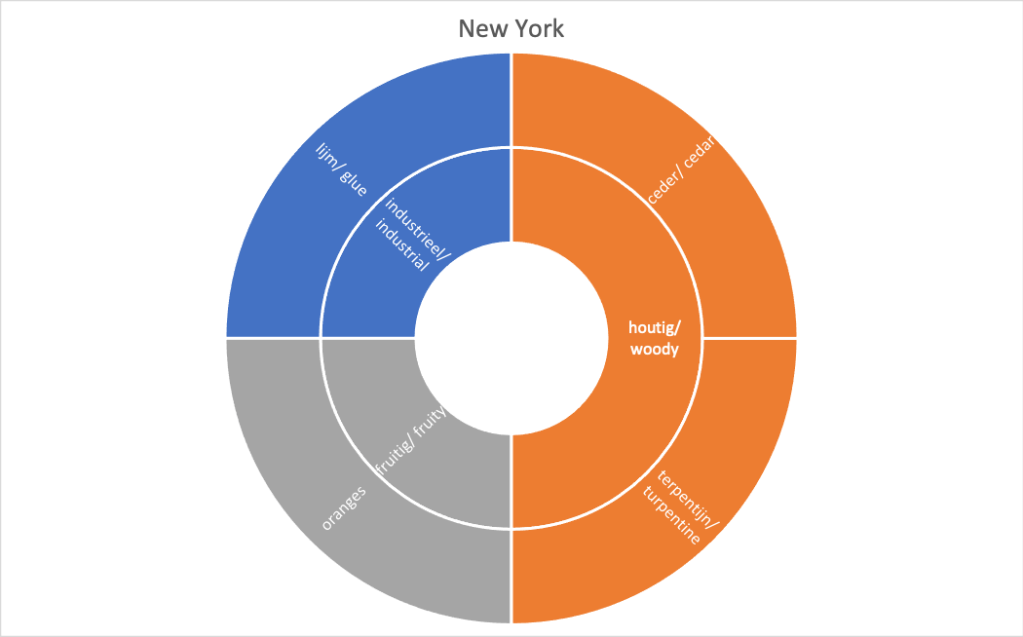

Scent wheel Mondrian’s studio New York, ca. 1943, copyright Caro Verbeek.

Fleeing the Nazis, Mondrian arrived in New York in 1940 after a two-year stay in London. Here, free from the threats of war and persecution, his optimism flourished, influencing a dramatic evolution in his style. The city’s vibrant energy and boogie-woogie rhythms inspired him, and he began using tape as a new medium to make his compositions as dynamic as the music he danced to late into the night.

The invigorating scent of glue filled his studio more prominently than before, alongside the familiar aroma of turpentine. Gone were the smoky scents of coal; the new space had (scentless) central heating. However, Mondrian was not entirely at ease with modern technology: he disliked telephones and found radios complicated, though he cherished his record player. When not smoking a cigarette—which his doctor advised him to quit—his studio exuded a crisp, clear air, reflecting the lightness and simplicity of his abstract works.

This airy studio embodied the clarity and purity Theo van Doesburg had envisioned in 1930:

“An absolute cleanliness, a constant light, a clear atmosphere. […] One can certainly learn more from doctors' laboratories than from painting studios. The latter are cages that smell of sick monkeys.”

Van Doesburg never experienced the pristine scent of Mondrian’s New York studio, having died in 1931. Mondrian himself passed away in 1944 in Murray Hill Hospital, New York, leaving behind his unfinished masterpiece, Victory Boogie Woogie. This painting, a “love letter to the world,” now resides in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Its lingering scent of piney turpentine offers a fleeting glimpse into the atmosphere of his studio and life.

Credits:

The perfumes were created by Anh Ngo, Birgit Sijbrands, and Bernardo Fleming of IFF, based on research by Caro Verbeek.

An article on the topic appeared in Dutch here: Verbeek, C. (2022), “Kun je abstractie ruiken? – Hoe de geurtransities van Mondriaans ateliers zijn artistieke ontwikkelingen markeren (én bewerkstelligen)”, KM Magazine.

An article in French on the topic appeared here: “Le parfum, une machine à remonter le temps” (ook over ateliergeuren Mondriaan), door Lionel Paillès (29-03-2022) Le Monde

An Arte documentary in French and German on the Mondrian smells can be found here:

https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/105628-001-A/gymnastique/

The New York Times recently interviewed Verbeek on Mondrian’s studio smells: